What's in a Name: A Pinhooking Explainer

World of Whiskey

Starting with our very first bourbons nine years ago, Pinhook seized on the idea that, if it's handled nimbly, a good bourbon or rye can be made even better after it comes out of the barrel. This belief inspired us to source distilled whiskey from third parties, then focus on what came next--when the juice was ready, we used meticulous blending and proofing to turn out truly special vintages that showcased the best that every barrel had to offer.

This unique approach to making whiskey is captured right there in our name: Pinhook. For many people, including Pinhook drinkers, however, this might beg the question: What’s a pinhook?

Well, for starters, it’s generally not a noun. To pinhook means to buy something for a low price, hold onto it, and sell it once it’s become more valuable. The term has a long history in Kentucky, spanning the industries most closely identified with the state–tobacco, horse-racing, and now, whiskey. (There are theories about the origins of the term itself, but its true etymology has been lost to time.)

Read on to learn more about the Kentucky-based practice that gave our whiskey its name, and why the philosophy behind pinhooking is so important to everything we do.

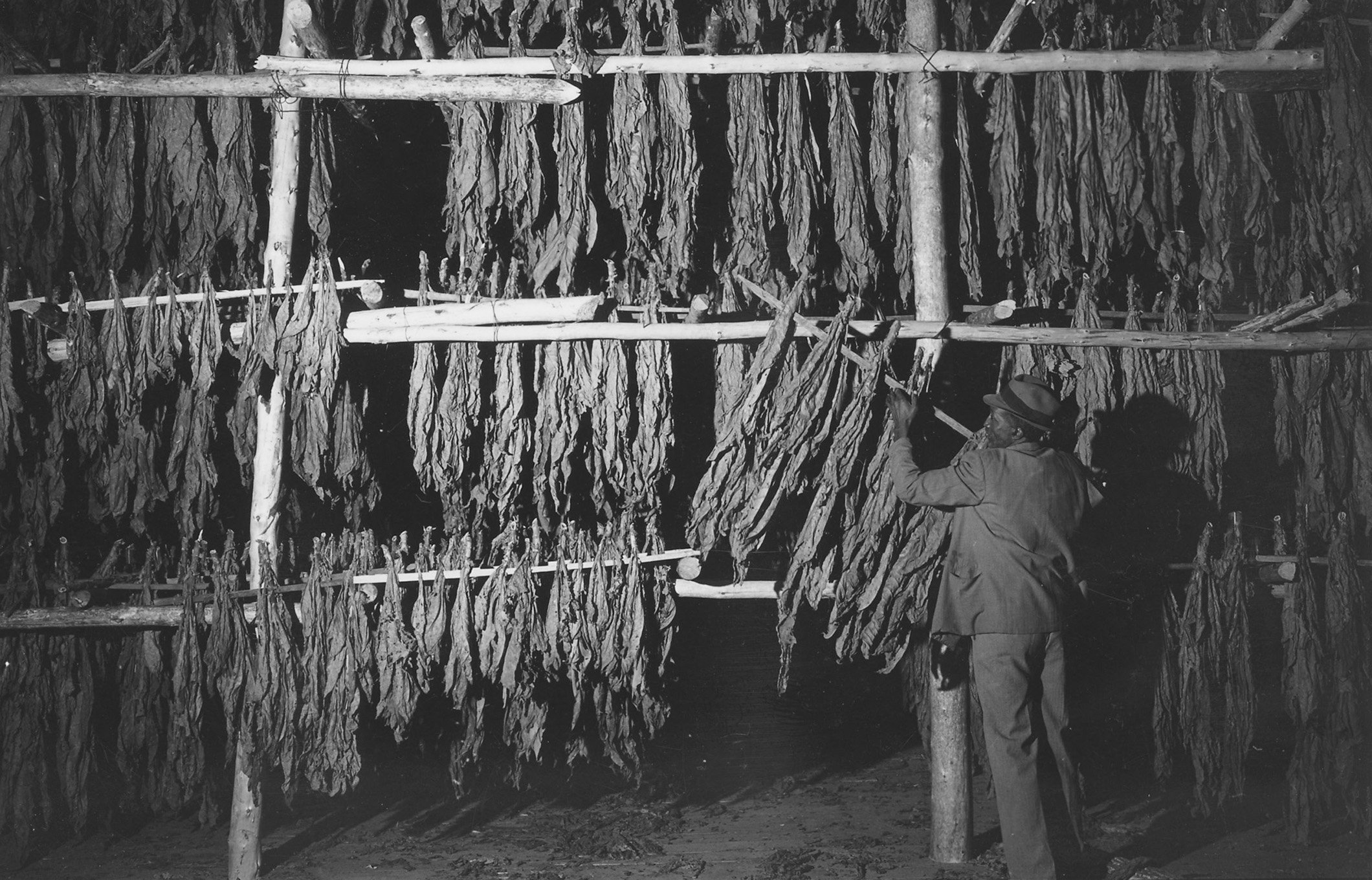

Tobacco Origins

To find the earliest origins of the term “pinhook,” you have to look to another high-profile Kentucky product, tobacco. Its dried leaves became the chief export of a young America, with the Bluegrass State eventually accounting for a majority of the output. By the 1800s, small-time speculators would buy tobacco from growers, then turn around and sell it at the tobacco markets, hopefully at a profit. These were the first pinhookers.

In its tobacco days, pinhooking was considered a seedy business, with pinhookers often misleading growers about the state of the market or quality of the crop in order to secure it for less than it was worth, and contributing no added value to the product itself.

That reputation would improve when the thoroughbred industry developed its own brand of pinhooking. The concept that originated in Kentucky’s tobacco fields translated well, it would turn out, to the world of thoroughbred racing.

Thoroughbred Pinhooking

Those of us who tune in once a year to be dazzled by the field of elite three-year-olds at the Kentucky Derby probably don’t put a ton of thought into how those champion racehorses got to this point. But those early years of a thoroughbred’s life are crucial to future success on the track. They involve risk, investment, know-how, and hard work–often in the form of pinhooking.

A horse can be pinhooked at one of two stages in its development. In the first, thoroughbreds are purchased as weanlings, or horses below the age of one. Over the course of the following year, they become accustomed to being handled and led by humans, and enter the early stages of training. If all goes well, these thoroughbreds are then sold at auction as yearlings for a profit.

In the second type of thoroughbred pinhooking, someone buys a thoroughbred yearling, then spends the following months seeing it through the process of becoming a racehorse. This includes breaking, or training the horse to allow a human to ride it. Pinhooked yearlings are sold again as two-year-olds, the age at which a thoroughbred’s formal racing career typically begins.

Unlike the old tobacco speculators, in the thoroughbred version pinhookers must have a great deal of skill, including a keen eye for potential on the racetrack and the ability to train a horse and guide it into the racing world. Pinhooking thoroughbreds isn’t for the faint of heart–insiders estimate that fewer than half of pinhooked horses ultimately turn a profit.

But when it works, the payoff can be huge–every year at the auctions, racehorses bought the previous year for say, $50,000, are sold as yearlings or two-year-olds for many times that amount. And at the racetrack, the strategy has brought horses to the pinnacle of the sport. Famous pinhooked thoroughbreds include Kentucky Derby winners Monarchos and Nyquist.

Whiskey Pinhooking

The 1800s had tobacco pinhookers, the 1900s had thoroughbred pinhookers, and now in the 21st century, we at Pinhook Bourbon have ushered in the whiskey pinhooker.

The whiskey pinhooking process echoes that of other industries by breaking whiskey production into stages of ownership. In this case, that means one party distills the whiskey, then another acquires that whiskey long before it is ready to hit the shelves. In the final stage, the second owners use blending and proofing to bring out the true magic of a great whiskey once it’s mature and ready to be bottled.

Whiskey pinhooking became possible thanks to the explosion in popularity of American whiskey over the past couple of decades. As more small brands entered the market, they looked to existing distilleries to source their barrels. In the early days, brands might try to downplay the fact that they weren’t distilling their own product, but more recently, the practice has gained legitimacy. Today, many notable bourbon and rye brands source their whiskeys from other distilleries. They are whiskey pinhookers, even if they don’t realize it.

We embraced pinhooking as a founding principle, going so far as to use the concept as our name. While Pinhook now uses a proprietary mashbill for its flagship bourbon and rye, both of which are distilled at Castle & Key Distillery in Kentucky, our ethos remains one of pinhooking–finding promising barrels, seeing them through to maturity, then blending and proofing to craft the best possible vintage every time. Many of our limited releases are still pinhooked today, including our Vertical Series Bourbon and Rye and Collaboration Series bottles.

The pinhooking approach allows us to embrace our curiosity and creativity in sourcing, blending, and proofing to land on the closest thing to perfection in our bourbons and ryes. In the process, we’ve not only continued a time-honored Bluegrass State tradition, but updated it for another quintessential Kentucky industry.